In a corner of Western Avenue Elementary School’s yard, a dozen children excitedly circle Charles Evans at the end of their day. One child bounces a ball, another picks a handful of play slime out of a jar as the others chirp with enthusiasm.

While other children have gone home for the day, Evans rounds up this group who have no homes. He leads them down the street to South Los Angeles Learning Center, where he runs an after-school program for homeless children.

Almost 13,500 students out of around 680,000 in the LA Unified School District were homeless in the 2009-10 school year, a more than 50% increase from five years ago due largely to unemployment and foreclosures.

The center run by School on Wheels used to open one day a week, but Evans now collects the kids daily after school for two hours, until their shelters open. The program got its name from the tutors who visit children such as Jayla weekly, in shelters, parks and libraries.

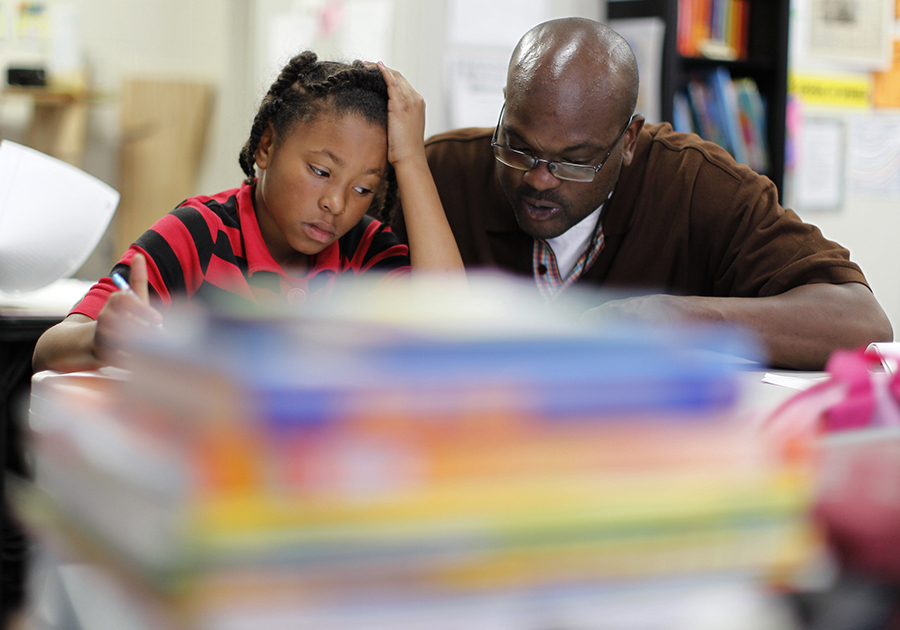

“When I first met her she was struggling quite a bit,” says Evans, who came across Jayla in two different shelters. “She has been living at the Midnight Mission now for about five to six months. And just that stability alone, has allowed her to focus on school.”

The day before I visited Jayla in her shelter, her mother Rosonia received a letter from school saying her daughter was recognized as a “gifted” student.

School on Wheels works with 6,000 kids a year, about half the homeless children in LA, and some results have been heartening. One alumnus is studying at Harvard, another at UCLA.

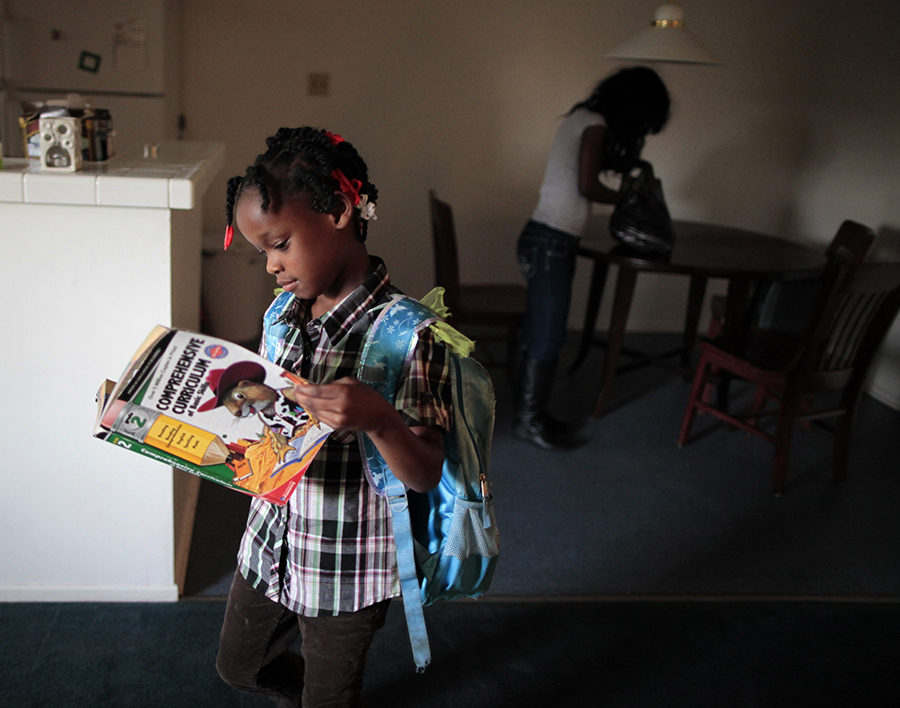

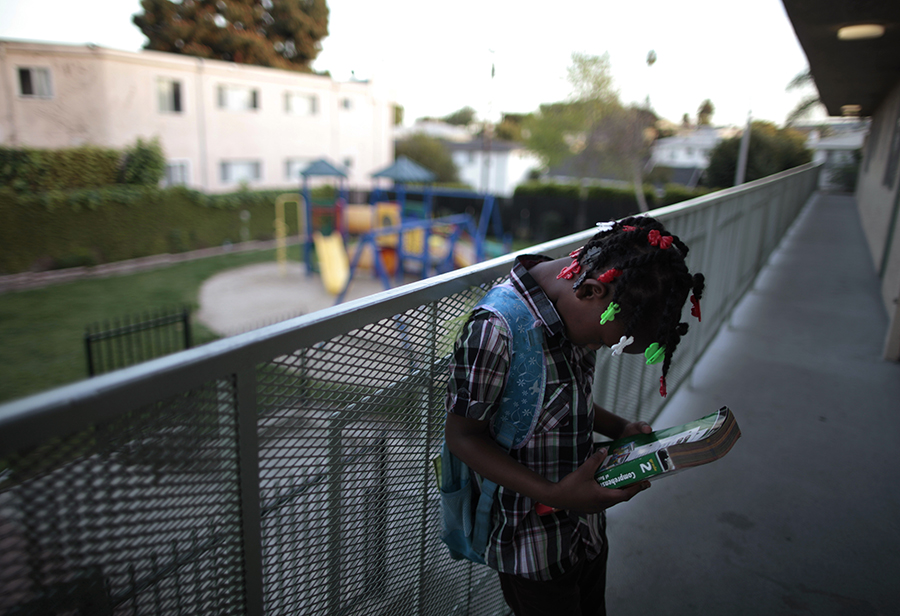

“That’s one of the challenges – to get the kids motivated to actually see the bigger picture, and realize that if they work hard enough they can achieve anything they want to achieve.”Six-year-old Alicia skipped the whole way back to her shelter after her homework session, laughing as Evans told her to slow down.

Four months ago, she could barely recognize the alphabet. Now she can read a whole book aloud. Alicia’s mother recently told Evans that her daughter’s teacher said she was the only child in the kindergarten class who could read a book from cover to cover.

“We try to instill confidence in the kids, and the more they read, the more their self-confidence and self-esteem goes up,” says Evans.

But the difficulties are imposing. Homeless children move around a lot, and often end up in noisy, crowded shelters. Most don’t have parents who help with homework.“Schoolwork for our kids becomes a lot less important, and they tend to take on the burdens and responsibilities of their parents,” Evans says. “We’ll ask the kids what they want in life, and most of the time they want things for their parents. They’ll want a new house or a car or more money so their mom won’t have to struggle as much.”

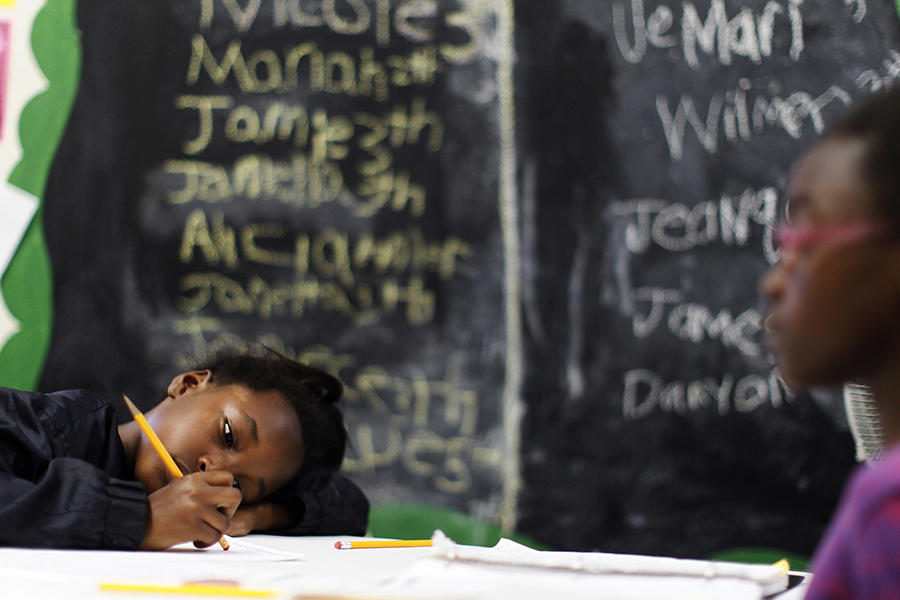

Those concerns are not on display in the cozy former storefront that serves as the classroom. Despite a cacophony of voices simultaneously reading aloud from different books, Jamella, 8, focuses intently on her math homework using an abacus. Jeanquis, 6, goes outside to jump rope with some other kids.

Word of School on Wheels has spread to other children. Friends of the kids in the program have asked Evans if they can come along. He tactfully promises to speak with their parents, not wanting to tell them he only takes homeless children.