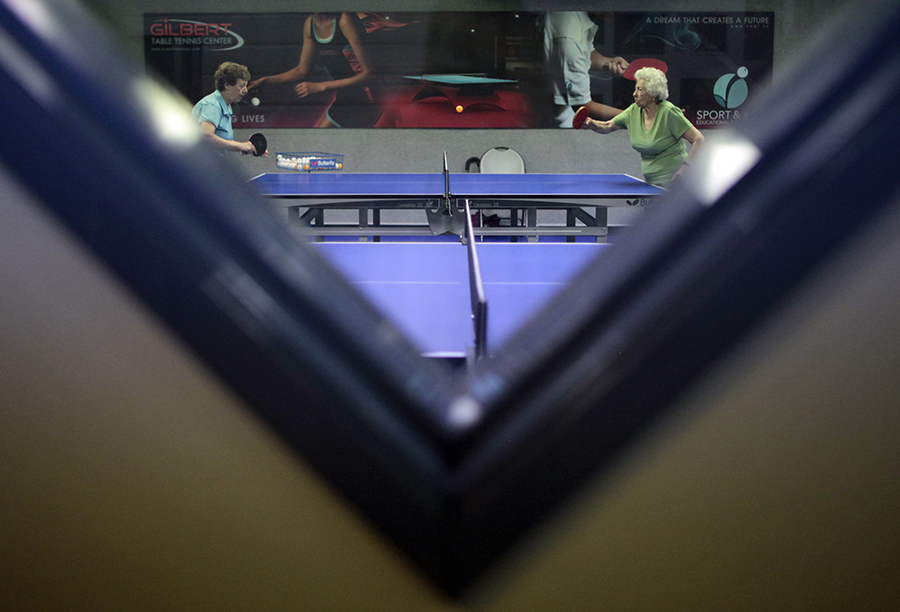

Holocaust survivor Betty Stein, 92, takes off her cardigan. She squares up to the table, bat in hand, deep in concentration. Her eyes dart rhythmically in time with the clack, clack of the ping pong ball.

At the next table, Eli Boyer, 91, sings a love song in Spanish as he plays. The retired accountant speaks four languages, and flits between Russian and English with his coach Elie Zainabudinova. As long as the ping pong ball ricochets back and forth, their absorption is total. Flashes of their former lives creep across their faces – laughter, determination, a mischievous grin.

Only when they sit down do their eyes give it away. The tell-tale existential terror of Alzheimer’s. The confusion. The forgetting of who they are.

Stein and Boyer are among one hundred participants in a ping pong therapy program for people with Alzheimer’s and dementia at the Arthur Gilbert Table Tennis Center in Los Angeles.

Founder Mikhail Zaretsky says the sport does not cure, or even slow down the disease, but helps the 100 participants by raising their heart rate and the blood flow to their brains, and exercising them mentally as well as physically. He says it helps their depression, improves their balance, and makes them more alert.

Alzheimer’s erases memories and robs the brain of its ability to learn. A 1997 Japanese study touted the benefits of table tennis for Alzheimer’s and dementia patients.

Betty has been playing ping pong weekly for almost a year now. When she arrived she could barely keep a rally going for three or four strokes; now she’s hitting 20 or 30, says Zaretsky. “After she started playing ping pong, she was telling her caregiver stories that she hadn’t ever told before,” he says. “She told her more details on how she survived the Holocaust – how she had to hide for a few days behind a stove.”

“This was amazing, and some doctors suggested maybe she was depressed, and when she started playing ping pong maybe the depression went away a little bit. We don’t know exactly.”

Zaretsky also takes the program to seven nursing homes in the Los Angeles area. He hopes to use the program as part of a U.S. study on the benefits of table tennis for Alzheimer’s and dementia patients.

Boyer’s wife Michele, who has been married to him for 50 years, noticed his dementia starting five years ago. “On the days he plays he’s more alert, he’s happier, he walks faster and his comprehension is a little more in memory for that day. It’s a little surprising, but you can really see it. And it gives him a sense of pride in himself.”

“I’m holding it right, I’m holding it right, that’s what I’m going to do,” chants Boyer repeatedly to the rhythm of the ping pong ball. “You’re gripping the racquet like the Chinese,” reassures his coach. “Chinese players do that.”

She asks him to sing a song in Russian. Boyer breaks into “Besame Mucho,” a Spanish love song. In his clear voice the lyrics continue to roll as he keeps the ball in play to a different beat.